There is a staggering amount of chatter and ink spilled about resilience, grit, and so forth as it relates to the process of building a startup. Less chatter about building a venture fund, though the grit and resilience for emerging managers is implied to the point that it doesn’t get written about as much. (More on this later.)

Something I haven’t written much about yet is my background in the music industry. I haven’t written about it because there isn’t that much to write about.

An almost-career in music

Through college, I volunteered as a Production Assistant at a beloved Los Angeles-based public radio station called KCRW. I spent countless hours volunteering on radio shows, answering phone calls from subscribers, supporting live events, and more, not to mention the hours spent on the 405 freeway driving to and from the station and various concert venues. I applied for a full-time role upon graduating from college, but the station hired someone who came with real, full-time radio experience (and turned out to be the right hire). Because I wasn’t selected, I found my way to tech and the rest is history. TLDR; if they had hired me, I wouldn’t be a VC today.

In parallel to my volunteer days at KCRW, I started dating a songwriter and band leader who I would later marry and move across the country with. He’s now a full-time songwriter, producer, and frontman to a rock band.

Every so often I’m reminded of the parallels between the plight of the music artist and that of the entrepreneur.

One big takeaway from my occasional proximity to the music industry: No one has thicker skin than a music artist.

Quality products do not beget eyeballs, at least not at first

Allow me to paint a picture.

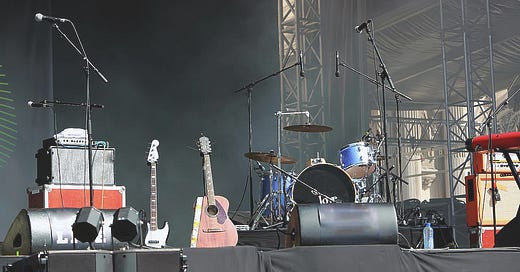

Imagine writing a song. Imagine pouring a tremendous amount of time into honing your craft, mining the depths of your soul for a hard-earned life lesson or insight, then turning that kernel into a creative work — an original song. Then, you spend your personal money recording this song, mixing and mastering the song, then finding a venue to perform this song (and others).

You practice, then you practice some more. You rally a band. You pay to have photos taken. You create social media posts, scrutinizing the text, hashtags, photo, and time of day to post. You share links with your social media following to buy tickets for your show. You haggle with the venue over what percentage of ticket sales you get to keep to recoup some of the costs. You pull together some merchandise and convince someone to hold the Square reader and process sales for t-shirts and stickers.

It’s show time. Your band is ready. You hear there will be music industry people in the audience.

You are onstage performing. What happens? Everyone is perfectly silent and hanging on every word and note played by you and your band, loudly applauding after each song.

Just kidding — half of the people are loudly talking over you through most every song about what they had for lunch that day.

Immediate feedback loops = a humbling experience

Artists have incredibly thick skin. They have to. If they didn’t, they would give up.

This immediate feedback loop is different from the experience of a tech entrepreneur taking a website live and eagerly awaiting clicks and email signups. Why, you ask? Because this vulnerability (on behalf of the entrepreneur) and negligence (on behalf of an audience) happens behind the veil of the internet.

When you are an artist performing on stage, tuning your guitar for the next song, you can audibly hear your audience not caring about the difficulty of the process that led you to that very stage. It is immediate feedback. It is highly vulnerable.

It also reminds me of working in restaurants through high school and college. A restaurant owner has to build a restaurant space, find suppliers, hire a team, design a menu, get permits signed off by the city, then perhaps put out a sandwich board and eagerly await some passerby who is willing to stop in for a bite.

There is a vulnerability experienced by entrepreneurs everywhere, though the immediate feedback loops are the hardest. They are the fastest no’s, the most obvious objections.

And, even worse, the feedback loop could be wrong. Perhaps the people loudly talking are not your audience (most likely they aren’t), but your audience exists elsewhere and would be thrilled to hear your song. It becomes a matter of believing in the long game, in not allowing the chatter to eat you alive.

Or perhaps the people talking loudly in the audience are gatekeepers in that industry. This always hurts. Yet, it doesn’t matter. They might not matter so long as you can find your true audience elsewhere, and that audience produces revenue. Then all of a sudden, the gatekeepers will take notice. Sometimes they take notice in a big and life-changing way.

Support your fellow risk-taker

In conclusion, if you are in an industry requiring thick skin for survival, be kind to your fellow artist. Your ability to listen to their song and not talk over them while they are onstage is a form of paying it forward that may seem intangible in the moment, yet is substantial.

Be a good listener. Until next time.